The Day My Environment Became the Problem

The difference between Poetry and Conda became clear to me the day my Python environment stopped being “just Python.”

For a long time, I thought my problems were about code.

When something broke, I assumed it was:

- a bad dependency,

- a missing version pin,

- or a mistake I made at 2 a.m.

What I didn’t realize was that my environment itself had quietly become part of the problem.

That realization didn’t come from a crash.

It came from waiting.

Watching a terminal sit there, stuck on “Solving environment…”, while I wasn’t even sure what problem it was solving anymore.

That’s when I started noticing the difference between Poetry and Conda wasn’t about features.

It was about what kind of world each tool assumes you live in.

How Conda Entered My Life Without Asking

I didn’t choose Conda.

Conda showed up.

It was already installed on the machine.

It came with the data science stack.

It “just worked” — and for a while, that was enough.

Creating an environment felt serious. Heavy. Capable.

# Creating and setting up a Conda environment

conda create -n ml-project python=3.10

conda activate ml-project

conda install numpy pandas scikit-learn pytorch cudatoolkit=11.8

# Solving environment...

# (30–60 seconds later)Nothing here is wrong.

But it quietly communicates something important:

This environment is not disposable.

Once it existed, I hesitated to touch it.

I avoided rebuilding.

I worked around problems instead of resetting.

That hesitation mattered more than I realized.

When “It Works” Started Feeling Expensive

Conda environments tend to grow.

One package leads to another.

One channel pulls in more system-level dependencies.

Suddenly the environment isn’t just Python anymore.

It’s:

- CUDA

- system libraries

- compiled binaries

- cross-channel constraints

That’s powerful — but power comes with weight.

I was afraid of rebuilding the environment.

That fear changed how I worked.

Poetry Came From the Opposite Direction

Poetry didn’t arrive bundled with anything.

I installed it deliberately.

The first time I used it, the contrast was immediate.

poetry new api-service

cd api-service

poetry add fastapi uvicorn pydantic

poetry installNo solver drama.

No channels.

No system-level surprises.

I stayed in the same mental context.

I didn’t stop thinking about my application.

That felt… lighter.

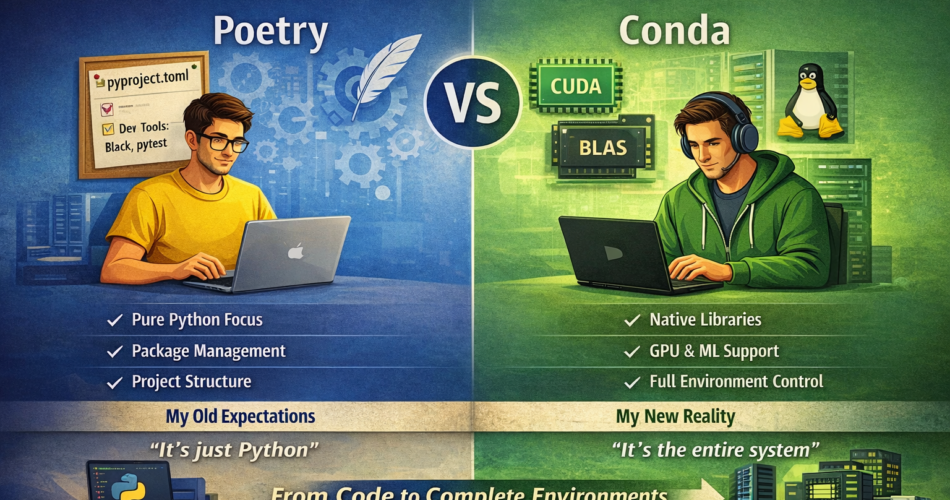

The First Real Difference: Scope

The core difference between Poetry and Conda isn’t speed.

It’s scope.

Poetry assumes:

- You’re managing a Python project

- Dependencies are Python packages

- The environment exists to serve the project

Conda assumes:

- You’re managing a computational environment

- Python is one component among many

- The environment is the product

You can see this clearly in configuration.

Poetry’s world (pyproject.toml)

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.10"

fastapi = "^0.104.0"

uvicorn = "^0.24.0"

[tool.poetry.group.dev.dependencies]

pytest = "^7.4.0"Everything here is Python.

Nothing leaks beyond the project boundary.

Conda’s world (environment.yml)

name: ml-project

channels:

- pytorch

- nvidia

- conda-forge

dependencies:

- python=3.10

- pytorch

- cudatoolkit=11.8

- numpy

- pandas

- pip:

- fastapiThis file already tells a story:

multiple ecosystems, multiple solvers, multiple sources of truth.

Neither is wrong — but they optimize for very different realities.

Where Each Tool Started to Crack

Poetry cracked first when I needed non-Python dependencies.

CUDA.

System libraries.

Binary compatibility.

Poetry doesn’t want to be responsible for that — and that’s intentional.

Conda cracked when I wanted fast iteration.

Quick rebuilds.

Throwaway experiments.

Short-lived branches.

CI environments that should behave exactly like local.

Waiting for a solver to decide my fate became friction.

They just stopped matching the way I worked.

The Mistake I Actually Made

My mistake wasn’t choosing Conda.

My mistake was using Conda for things that wanted to be disposable.

I treated environments like pets:

carefully maintained,

never destroyed,

slowly accumulating state.

Once my workflow became CI-driven and iterative, that model stopped working.

Poetry encouraged the opposite behavior:

rebuild freely,

lock deterministically,

treat environments as replaceable.

That shift mattered more than features.

What I Do Now (The Resolution)

I stopped asking “Which tool is better?”

Instead, I ask:

“What am I optimizing for?”

- If I’m working on ML, GPUs, system dependencies → Conda

- If I’m building services, libraries, APIs → Poetry

- If I expect frequent rebuilds → Poetry

- If I need ecosystem-level control → Conda

This isn’t indecision.

It’s clarity.

How This Shows Up in CI

Poetry-based projects feel predictable in CI:

poetry install --no-interaction --no-root

pytestConda-based projects feel heavier — but more complete.

The key difference isn’t reliability.

It’s expectation management.

CI behaves best when the environment model matches the workflow.

Conda vs Poetry: How It Played Out for Me

| Aspect | Conda | Poetry |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | System + Python | Python-only |

| Solver behavior | Heavy, global | Focused, project-scoped |

| Rebuild cost | High | Low |

| Environment disposability | Discouraged | Encouraged |

| CI iteration speed | Slower | Faster |

When Each Tool Makes Sense

Conda shines when:

- The environment is the product

- You rely on compiled, non-Python dependencies

- GPU and system libraries matter

Poetry shines when:

- The project is Python-first

- Environments should be cheap

- Reproducibility matters more than ecosystem breadth

Final Thoughts

The difference between Poetry and Conda isn’t about winners.

It’s about intent.

Conda builds worlds.

Poetry builds projects.

Once I stopped forcing one to behave like the other, my environments stopped fighting me.

And the moment environments stop demanding attention,

you get back to what actually matters:

writing code that moves forward.